- Jul 01, 2025

Can AI Revive the Ainu Language Japan Tried to Erase?

- Jul Tue, 2025

- in Tech

Can AI Revive the Ainu Language Japan Tried to Erase?

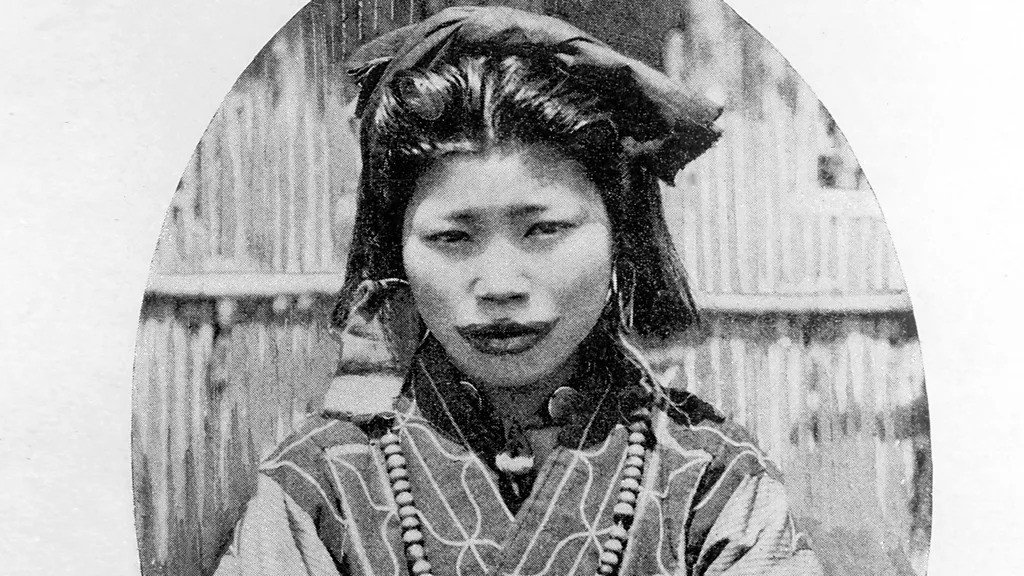

More than a century after colonisation pushed the Ainu language to the edge of extinction, artificial intelligence may now be its unlikely saviour. A new generation of researchers and Indigenous advocates are using AI tools to preserve, synthesise, and revive the critically endangered language once nearly erased by Japanese state policies.

In the northern regions of Japan, Maya Sekine grew up hearing bedtime stories in Ainu, the language of her ancestors, told through cassette tapes played by her father. Her favorite was about a singing Hokkaido wolf — an enchanting mix of melodic Ainu phrases and playful barking. But as she grew older, it became clear that very few around her understood these words. Ainu was disappearing.

Declared critically endangered by UNESCO, the language once had around 15,000 speakers in 1870 — a year after the Ainu heartland of Ezo (now Hokkaido) was annexed by Japan. By 1917, that number had plummeted to just 350. Today, only a handful of native speakers remain. The decline was fuelled by decades of state suppression, including a ban on speaking Ainu in schools.

But now, a new hope emerges from an unlikely ally — AI.

Giving a New Voice to an Old Language

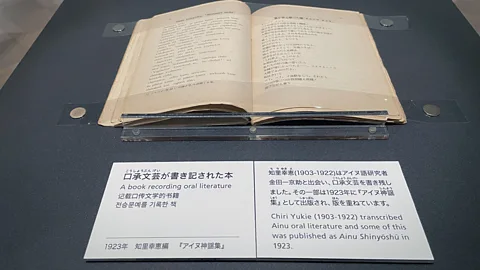

With support from the Japanese government and cultural institutions, researchers are digitising hundreds of hours of old cassette recordings — folk stories, chants, and prose narratives — and feeding them into advanced speech recognition systems. One such effort, led by Professor Tatsuya Kawahara of Kyoto University, is pioneering an AI system capable of recognising and even speaking Ainu.

The team used about 40 hours of audio from eight speakers, including folklore prose called uwepeker, provided by the Upopoy National Ainu Museum and the Nibutani Ainu Culture Museum. These archives — many recorded under imperfect conditions — now fuel a cutting-edge speech synthesis model. The AI has even generated voice renditions of two ancient stories: Tale of Bear and Raijin’s Sister. The result is uncannily lifelike, mimicking the cadence and tone of elderly native speakers.

"The sound quality of the old tapes was a challenge," says Kawahara, “but our technology has largely automated the process. We now have 300 to 400 hours of data."

The accuracy is impressive: the AI recognises Ainu phonemes with up to 95% accuracy in some cases, and has a word recognition rate comparable to that of a graduate student studying Ainu.

Cultural Caution Meets Technological Optimism

Despite the excitement, there’s a cautious tone among Ainu advocates. Sekine, who runs a YouTube channel teaching conversational Ainu, worries about mispronunciations or synthetic errors. “It’s more important to get and verify living data,” she says, emphasising the need for real-world use and understanding of the language.

Her father, Kenji Sekine, a Japanese Ainu language teacher, has been deeply involved in the AI initiative and helped source recordings. He’s hopeful. “It’s my life’s work. I want more people to learn. I think the [AI project] is a good thing.”

But systemic challenges remain. Though Ainu was recognised as a second national language in 2019, it’s still absent from the Hokkaido school curriculum. According to Hokkaido University’s Hirofumi Kato, this reinforces a monocultural education model that excludes Indigenous history and identity.

Technology Must Serve the People

Experts in digital linguistics argue that AI language projects should always be driven by the communities they aim to support. “In an ideal world, language technology is done by the speakers, for the speakers,” says Francis Tyers, computational linguist at Mozilla Foundation’s Common Voice initiative.

Whether in Catalan, Basque, or Sámi, successful preservation efforts empower communities to take charge of their language futures — not just as beneficiaries, but as creators.

In Japan, the Ainu AI initiative is still evolving. Kawahara's team hopes to capture more dialects and even enable virtual Ainu avatars as language tutors. But even as AI advances, its long-term success will depend on the strength and agency of the Ainu community itself.

For Maya Sekine, the story is both personal and political. “Language is the most important thing for us. It’s the connection between our culture and values,” she says. And with AI, that voice — once nearly silenced — may finally sing again.